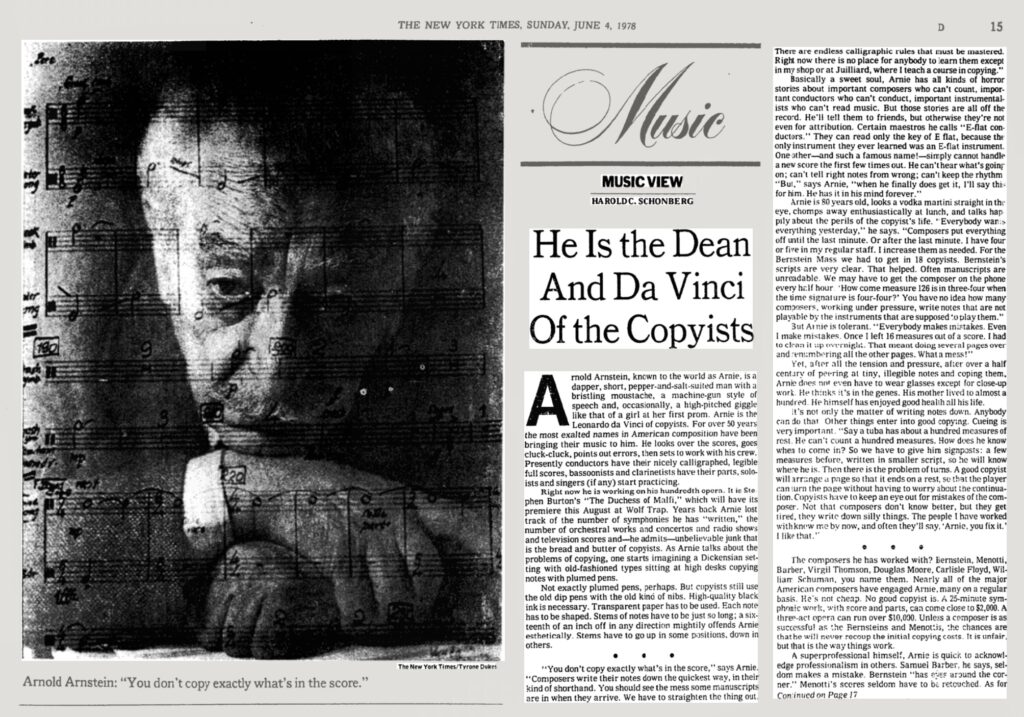

In my last blog post, I offered the transcription of a portion of a conversation with my mentor Arnold Arnstein. He was one of the most important figures in the New York City music-copying business back in the day when that work was still done primarily by hand. As a measure of his renown, he was profiled in the New York Times, June 4, 1978, by the paper’s senior music critic, Harold C. Schonberg, in an article that began like this: “Arnold Arnstein, known to the world as Arnie, is a dapper, short, pepper-and-salt-suited man with a bristling moustache, a machine-gun style of speech and, occasionally, a high-pitched giggle like that of a girl at her first prom. Arnie is the Leonardo da Vinci of copyists.” Schonberg’s affectionate profile is well worth reading in full (reproduced here at the site of one of Arnstein’s former apprentices, Kenneth Godel: https://www.musicpreparation.biz/arnie)

When Arnstein died in 1989, the music remaining in his office was deposited in the New York Public Library and archived as the “Arnold Arnstein Collection of Musical Scores, ca. 1950-1989.” According to the description at the NYPL website, “The composers represented in the collection are a cross section of contemporary composers of the 1950s through the 1980s as well as several pre-twentieth century composers. There are a number of composers associated with film or television (Alfredo Antonini, Sol Kaplan, Samuel Matlovsky, and Marc Wilkinson), and also several associated with the Broadway stage musical and popular song (Don Pippin, Charles Strouse, Alec Wilder, and Meredith Willson).”

One other composer’s name stood out for me—Charles Mingus. As you’ll see below, from another part of our conversation, Arnstein spent time with Mingus working on the score of one of his pieces. I like to fancy it might have been the same bundle of pages that’s now in the library collection—the manuscript score of Revelations for jazz ensemble, the piece done at the mid-1950s Brandeis festival described below—perhaps exactly what Arnstein had in hand when he climbed the stairs to Mingus’s apartment. Here’s Arnie talking about the experience in his own words (acknowledging that he and Mingus didn’t start off on the right foot!):

You take, for example, a man like Charlie Mingus who just died recently. He was tremendously respected by the jazz field. Seriously. I did a job once with Charlie. I had never heard of him until I got the score. And it was for the first Brandeis new music festival. Suddenly Arthur Berger [of] the music department at Brandeis—by the way, Arthur Berger wrote me up in the Herald Tribune of 1954, for the first time I ever got a write up. (Now I’m giving him publicity.) He’s still with Brandeis. [He] sent me two scores, one by Milton Babbitt and one by Charles Mingus. Milton Babbitt’s score was professional and there was no need of asking any questions. It was a straightforward—“Jazz Set” it was called—and we copied it. But Charlie Mingus, that was a little different. I had never seen—and by that time I was already in copying for about thirty-five to forty years—I’d never seen anything like this in my life. So, in order to get some of these things explained, I called Mr. Mingus on the telephone, asked him and told him I had this score and I was doing a job for the music festival at Brandeis, and would he give me some time, I’d like to ask some questions. Charlie hung up with the words “I got no time to teach you jazz.”

I’ve reported here the entire conversation between Charles Mingus and myself. Three days later I get a call from Arthur Berger, who had given me the score originally, and asked if I was anti-Negro. Apparently, what happened was, Charlie either misunderstood what I said or didn’t feel like cooperating, called Gunther Schuller on the road who was then—Gunther was then with the Metropolitan as a horn player—and complained about me … I said to Arthur, “Look you gotta come down here and look at this score.” I said, “You’re the professor of music, you explain it to me.” Arthur … came down the next day to my home and I put the score on the piano and I said “Well, Arthur, you tell me what this is all about.” Well, he knew this was all hieroglyphics and very difficult to understand and, in most cases, wrong—things out of range. I said, “Look, get me an audience with this guy and then we can move ahead.” Which he did.

So next day I went down and climbed five flights of stairs after two or three record companies on the second and third floor I finally reached Charlie’s apartment. At any rate, I brought my score, a print of it at least, with a red pencil, and I was going to ask Charlie all kinds of questions. And you, at the beginning, you could have cut the atmosphere with a knife. I proceeded to ask two or three questions and Charlie, ebulliently, suddenly said, “Hey, I’m going to take notation from you!” because of the questions I asked. I said “Look, that comes later. Let’s fix this up.” So he rushes to his wife and shows her what I’ve found. He says, “Look what the man found. What kind of eyes you got?” “Well,” I said, “you know, the usual kind. They see pretty well.” Well, in four hours we went over the score and we had sixteen out of the fifty pages done. We put everything in range. You know, the bassoon doesn’t go below B-flat and the viola doesn’t go below C unless it’s retuned, which wasn’t the intention, and so forth. And there were many more idiosyncracies that I can mention without becoming complicated. But at any rate, all of a sudden he says “Look, that’s as far as I can go now. We’re both tired. I want to take notation lessons from you.” I said again, “That comes later.” He says, “I’m coming up your way tomorrow,” and all of a sudden he had time to teach me jazz. Well, Charlie and I became, you know, very first name basis in about three seconds. We maintained a relationship until he died recently, at least telephonically. I did another small job for him later. Charlie was quite a guy.

NEXT TIME: more stories from my conversations with Arnold Arnstein.