A key part of my musical autobiography, one I have almost never mentioned in my bios, is music copying. Of course, a composer copies music by necessity, inscribing the notes and other symbols on the blank page, making them legible, accurate, and communicative. At one time, not that long ago, before personal computers became a ubiquitous part of our lives, all that was done by hand, either with pencil or ink directly on paper, or by engraving a metal plate with punches and scrapers. I have always loved the tactile aspect of marking a page, of creating a graphic composition that happens also to represent a detailed set of complicated instructions for the musicians.  The layout of a score is an analogue of the sonic musical space. Beautiful calligraphy expresses visually the music’s emotive power.

The layout of a score is an analogue of the sonic musical space. Beautiful calligraphy expresses visually the music’s emotive power.

One of my early prized possessions (as a junior high student, perhaps?) was a miniature score of Brahms’s Second Symphony. I wrote my name on the title page. It was a small paperback book, just five by seven inches, 148 pages long, with every note of every instrument lined up in the proper place, each system of the score showing only the staves for the instruments playing at that particular moment. I wanted to make little books like that. Was that one of the things that pushed me to be a composer?

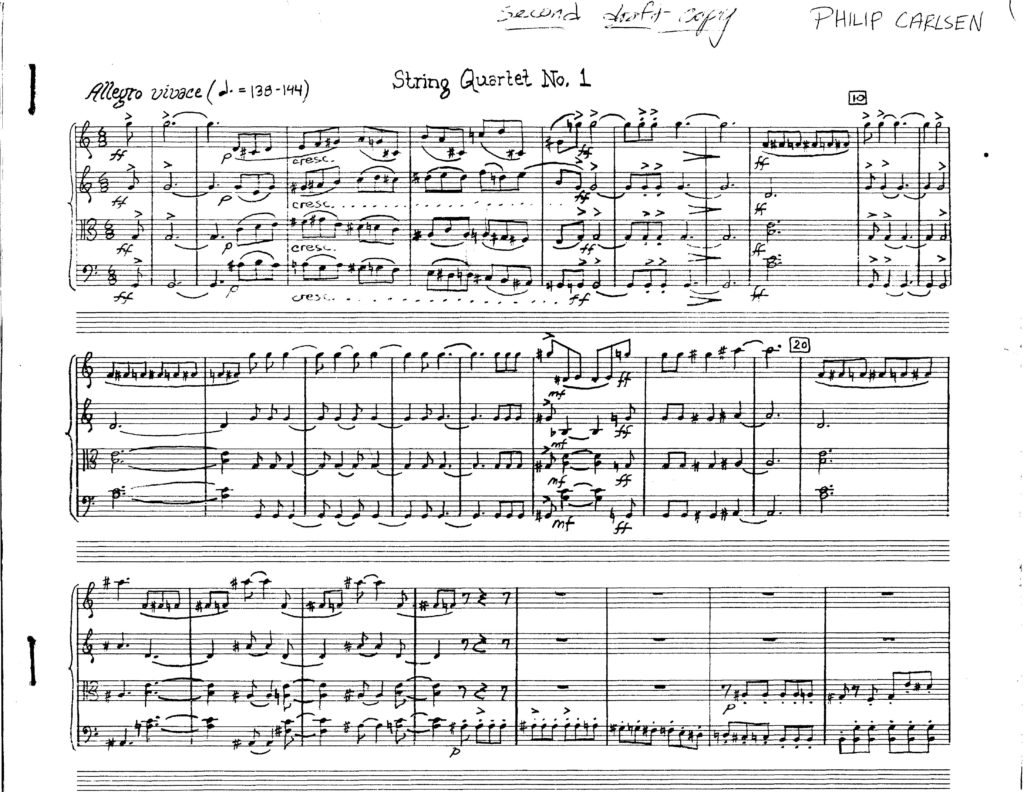

As I explored the stacks of the music library at UConn, where my dad taught for four years while I was in seventh through tenth grades, I discovered Bartok’s string quartets and listened again and again to them while following the scores. We moved to Seattle when I started eleventh grade, and it was there that I began composing a string quartet of my own, naturally very Bartokian. The only things I’d written up to that point were little piano pieces. I finished a movement, copied it out very carefully, and Dad arranged for his colleagues, the Philadelphia String Quartet, to play through it, an experience so astounding to me that I could barely grasp what was going on while it was happening. I added a second movement and submitted it to a competition sponsored by the Seattle Music and Art Foundation. I won first prize and had the piece premiered in a concert at the Cornish School the summer after I graduated from high school. I felt as if I were truly a composer. My music notation at that point was clean and legible, but still the work of a novice. Here’s what the opening of the quartet looked like, written out when I was around 18:

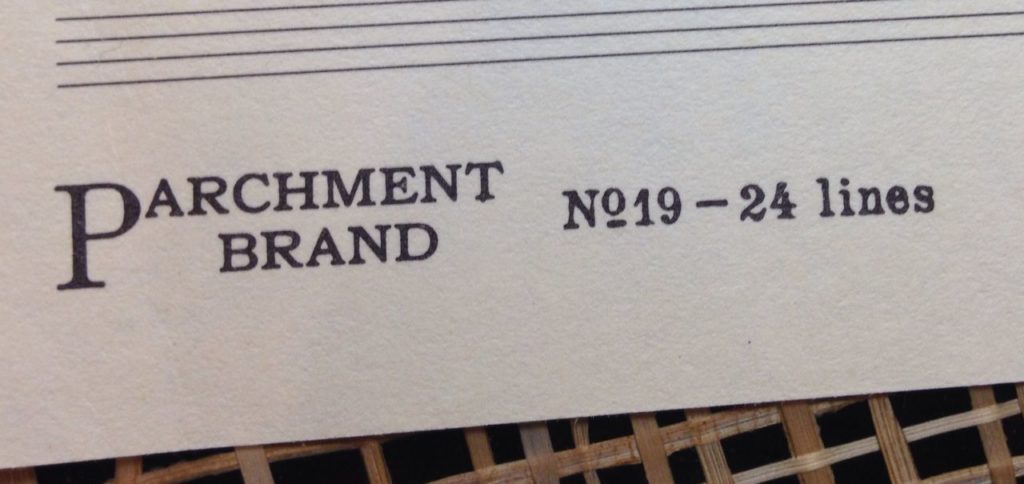

The paper I used for my quartet was Parchment Brand No. 19. It was thick and kind of creamy tan (like parchment), with no instrument names or clefs already printed on it, just 24 small staves with ample space between them, allowing plenty of room for ledger lines, and plenty of freedom to set it up however you wanted. You could fill a single page with a lot of music, such as five systems of string quartet music with a blank staff between each.  This was my go-to paper, in the same way that yellow legal pads were my choice in high school for prose writing. There was a music store in downtown Seattle that carried this paper. One day, I was poking around there and found a treasure on one of the back shelves: a ream of 30-staff paper, 14 by 18 inches, Passantino Brands No. 35. Now I could get really ambitious and start drafting some large orchestral works, striving for the same kind of thick, complicated visual textures that I was seeing in the scores of my hero Charles Ives. I worked for weeks on an Ivesian evocation of the woods behind our home in Connecticut, called The Fenton River Valley, nostalgically trying for my own take on Three Places in New England.

This was my go-to paper, in the same way that yellow legal pads were my choice in high school for prose writing. There was a music store in downtown Seattle that carried this paper. One day, I was poking around there and found a treasure on one of the back shelves: a ream of 30-staff paper, 14 by 18 inches, Passantino Brands No. 35. Now I could get really ambitious and start drafting some large orchestral works, striving for the same kind of thick, complicated visual textures that I was seeing in the scores of my hero Charles Ives. I worked for weeks on an Ivesian evocation of the woods behind our home in Connecticut, called The Fenton River Valley, nostalgically trying for my own take on Three Places in New England.

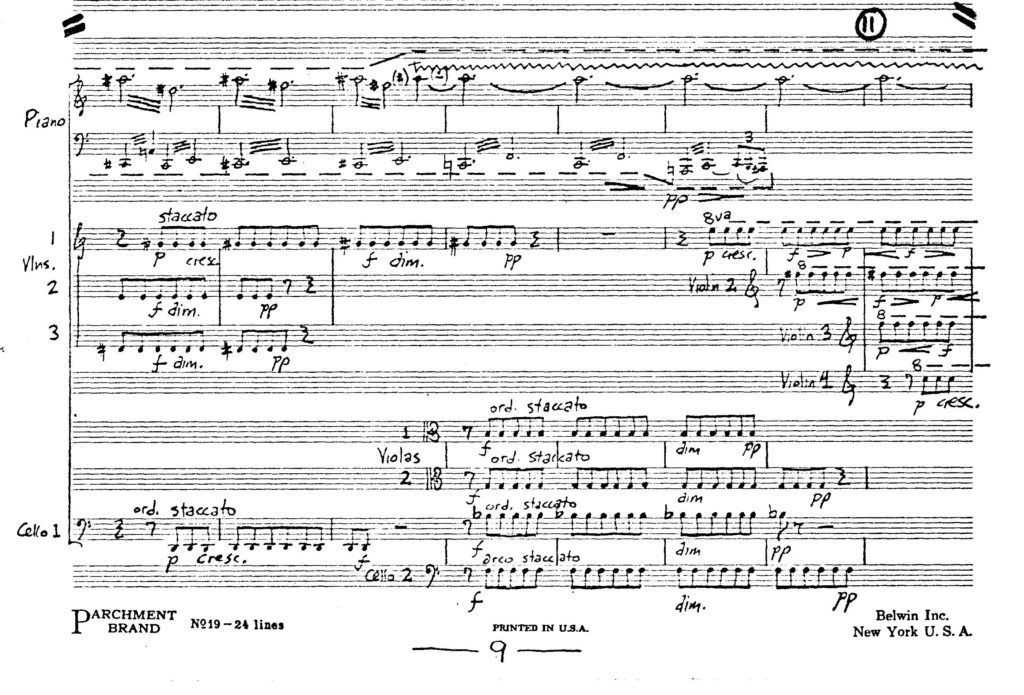

As a freshman, I methodically set about getting to know the music of Stravinsky. I was intrigued with the way he set up his later scores. Instead of marking bars of rest with a rest symbol, he would simply stop the staff when instruments stopped playing, and pick them up again further over to the right on the same page if the instrument came back in. Bar lines were set up like those in scholarly editions of Renaissance music, going between staves but not extending into the staves themselves, as if only hinting at the end of one measure and the beginning of the next. I tried that approach in my first big piece as an undergrad, Free Variations, a serial composition (on a nine-note row) for ten strings and piano. Here’s a system about one-third of the way into the piece:

NEXT TIME: Reminiscences about moving into music copying as a way to make money, first by preparing parts for my teacher, Bob Suderburg, then working for Arnold Arnstein in New York in the 1970s and early 1980s.